Published in Brian Wood Drawings, exhibition catalogue, 2019

My skeleton is laid out on cobalt blue cloth with all bones in alignment as if still connected by tissue, all my bones’ surfaces beautifully smooth, like yellowed ivory reflecting blue. The breeze feeling fresh and cool as it gently flows through my ribs and skull and around my bones. My consciousness is apart, in a gelatinous sphere, close and slightly above my body and yet everywhere in everything. This is exactly the same experience I’ve had in three near-death episodes in my life: awareness leaves my dying body to a precise location above, witnessing my body below, but consciousness becomes hyper-aware. It exists everywhere in every object, in every space, in every nearby being and mind.

This airy, open pleasure then collapsed groundward in crushing, dense compression. My body buried deep, squeezed by earth, face down, rotting flesh grown through with roots of trees, mycelia, and threads of grass, pervious to water and underground life. While I knew I was dead, I felt buried alive and tried to breathe. Facing down, with a tremendous weight of earth pressing my body tight, I couldn’t make my lungs work and felt I was inhaling mud and water in claustrophobic terror. I felt compassion for the trees and plants and worms that were moving through me, but sadness for my body having to suffer this gradual undoing. It felt too slow, too wet, too alone. I really didn’t like it and wanted to take my body out.

(Visionary experiences I’ve been blessed, or cursed, with since early childhood are nothing like normal discursive fantasy. Images arise suddenly, usually uninvited, with great intensity and an emphatic sense of being. Akin to hallucination but not, visions bring life and unknown knowledge to what is happening or about to happen, as if from some other world or dimension. Linear time is obviated so they can often be, or contain, pre-cognitions. Once present, their transformations can be affected but not controlled by inner or outer suggestion, desire, or wanting to know. When asked, consciousness usually moves, but in unpredictable paths that are rarely conjunctive. Resistance to fear, horror, pleasure, or even to resistance itself, often locks the mind in self-amplifying oscillations or narrowing repetitions as if in hellish halls of mirrors, killing vision. But a non-narcissistic request - in some traditions called prayer - moves and opens consciousness. The truly imaginal reveals its form and internal logic but refuses egoic agendas and reductive control. When making paintings and drawings, my consciousness opens itself to such visitations.)

From this pit I flashed up to high and light-filled space under the arching right transept of a tall and spacious cathedral. It seemed English Gothic, like Westminster Abbey. I looked down at my body laid out on a wheeled stone slab for its funeral. Dressed as a Hierophant in a brilliant cadmium red robe, covered with intricate gold embroidery of plants and vines and flowers, and wearing a tall bishop’s hat of a darker more earthy red, the center of my forehead looked up to the exact crossing of the transepts and nave. My body lay about thirty degrees off perfect alignment with the nave, the slab’s foot angled north. With arms out-stretched, almost forming a cross, but lowered thirty degrees like wings about to take flight.

At the interment, body and slab were inserted into a narrow wall cavity and the marble wall stone sealed in place. I felt a dark, dry claustrophobia with heavy stone squeezing my body and I knew I wanted out. Not to escape death, which I fully accepted, but wanting out of that confined permanence. Awareness yearned for another place.

With whirring rush of feathers in roaring air, I burst out in flight: a compact, dense brown owl with massive beating wings. Seeing in blackness, bright through owl eyes, I landed on the gutter of the verdigris roof of Chartres cathedral at night, just near a projecting gargoyle spitting into the darkness under moonlight. I lived as an owl but could also watch myself being an owl, feeling whole in a different body, comfortable in the dark.

As I felt the sensation of eyes flicking in my owl eye sockets, I remembered a recurring experience from my early childhood in Saskatchewan. I’d awake some mornings and be looking out past bone-hard circular sockets through the bright green eyes of an alien creature. Its pale grey skin held constantly shifting shapes – soft contorted slippages that didn’t correspond to any bi-symmetrical structure of earthly skeletal creatures. It had no bones. Feeling safe and protected, I’d say, “Oh, you’re back,” and would remain in that body all day. As I looked out, contrast and chroma were high, everything had a granular transparent beauty and the periphery of my visual field would dissolve into emerald green light. I felt fully in my being, my inner/outer world was one. We kept our secret.

Soaring up on my owl wings, I perched in the highest arch of Chartres’ right transept. Sunlight radiated rich color through stained glass roses as I marveled at the intricate incandescence of this pulsating space so rich with infinite detail and surfaces all alive. Very aware of the yellow-green spheres of my eyes under the perfect circles of feathered ‘eye-brows,’ I was painfully conscious of being inside my body looking out, incomplete in some way.

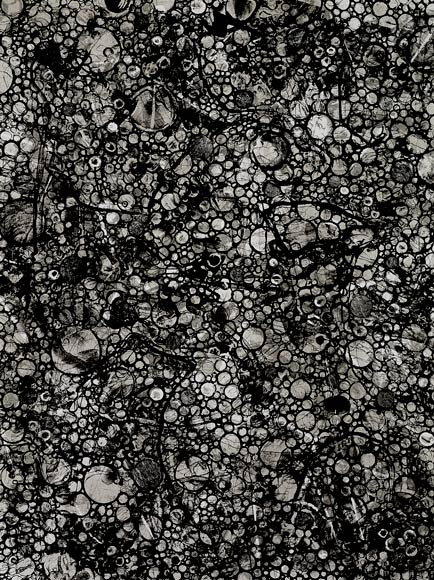

Instantly I was Chartres, shooting up and out of earth in driving speed and mass. A chthonic creature of tremendous power pulling darkness and light to the highest realms. Growing the history of everything into articulate piles of thought, density, and endless surface; rushing up in color and light; darkness so brilliant; time and space defined and obliterated. Awestruck by the beauty and richness of my surface and space, I completely surrendered to my being. Looking down, my belly a living limestone hive, I felt the lives and deaths of saints, living skin carved by human hands, shaped intensities of meaning and minds with their yearnings of love, ambition, awe, lust, hatred, and fear. The myriad eruptions of unearthly creatures and celestial color all grounded in stone. I wept with gratitude.

Once more, my disembodied consciousness saw my corpse laid out, this time in a ‘cradle’ of hammered-flat bronze strips. Shaped like the curved bovine horns of Hathor’s crown, each three inches wide, each with space between, they formed a long couch or cradle. The arching curves reached over my corpse and a channel of space ran underneath, centered up the bier. My body began to burn and as the flames grew higher my body rushed into intense ecstasy. Each cell exploded in flame and as the mass of flames grew so did the orgasmic euphoria that I knew contained all that ever was or could be. I felt each limb, each organ, every unknown part, burning in extreme joy and reaching out as fire. But my skeleton remained untouched and left behind on blue, the bones burnished like the ever-touched relic of some ancient saint or magus. As the fire grew, my watching consciousness joined the flames and became the fire and remained thus embodied.

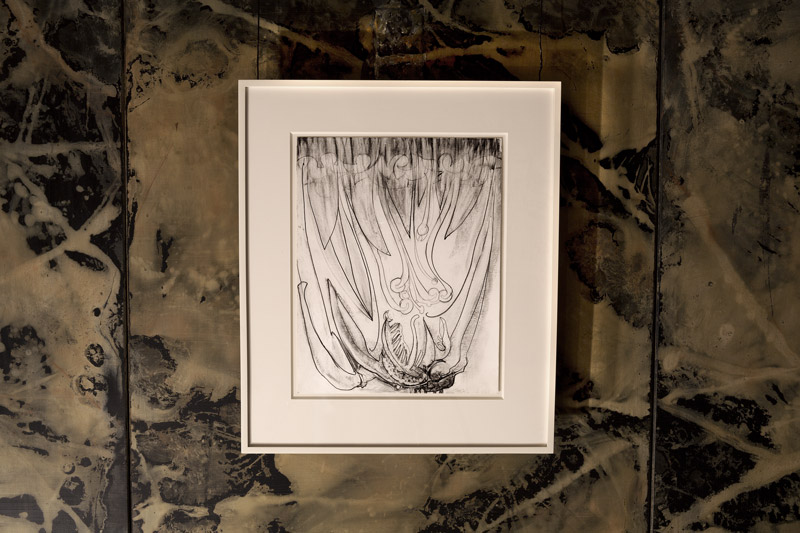

As a pillar of fire, with a pure sapphire center, surging, reaching, turning in complex form and gesture, shaped empty space or forms of detailed specificity, sharp-edged or gaseous but all the essence of flame, I moved through space and time. At one moment, I was in my studio working drawings and a large painting. As the conduit of forms moving through my flames with great energy, I made images directly on the linen without paint or tools with no hesitation or resistance. It all moved fast as light but felt eternal and still. Passing through linen surface, I was out in galactic space far beyond earth, as a roiling mass of fire, gliding at great velocity on curved invisible fields like grooves though immense space. I could feel the shifting gravitational fields as they weighted my fire, torquing through brilliant blackness – a darkness generating intense, transparent light but still the deepest of complex blacks. With profuse detail of structure and form, I saw billions of objects in such intricate detail, seemingly impossible for a single mind to perceive. I lived through births and deaths of stars, huge roaring explosions of supernova, rushing or sucking or bursting of space over immeasurable distances, eruptions and endless patterns of light, complex arrays of matter and whirling condensations, black holes, and vast distances of empty but living space. Extraordinary beauty and unbearable energy – but I experienced no fear. While moving near the speed of light, I had the sense that I am all of this, witnessing it all but containing it all, being it all, in complete silence and stillness.

After traveling for aeons I cried out, called and wept for my celestial twin, my angelic double, to reveal itself. I instantly saw a point of light in the distance and then a leg or arm with alternating foot or hand or a hybrid of both, reaching across millions of miles and beckoning me to follow. As I spun closer, near the edge of the universe inflating always beyond reach, I could see a simian-like creature gamboling in from beyond to meet me while still holding to the knife edge of space. It played and teased and stretched its limbs to me, reaching and retracting in elastic velocities over vast distances. Its body made of twining layers and bands of red-gold light, bands like muscles stretched over black interior space, a deep black emptiness revealed as its body opened and folded: no skeleton, no skin, no fixed scale. All sexes and no sex, its limbs and body stretched and pulled in humorous, boneless, irrational contortions. Always I could see two sensitive, brilliant eyes, glittering emerald orbs, coalescing to pale yellow where an iris might be, both perceiving and composed of light. Its head and face swarmed in protean flashes: faces replacing faces, multiple heads and shapes, creatures, animals, humans. Dog-like snouts with sharp pointed teeth, wolves and lions, my mother, lizards, insects, birds, monsters, my father – loving faces, violent faces, seductive faces, impassive faces, faces I knew, many I didn’t, lustful faces, angels, gods, beasts, devils, persons. And yet I knew I was all this: my twin’s body of light my most true reality. Its motility and grace, humor and sight, in constantly changing scale my truest being.

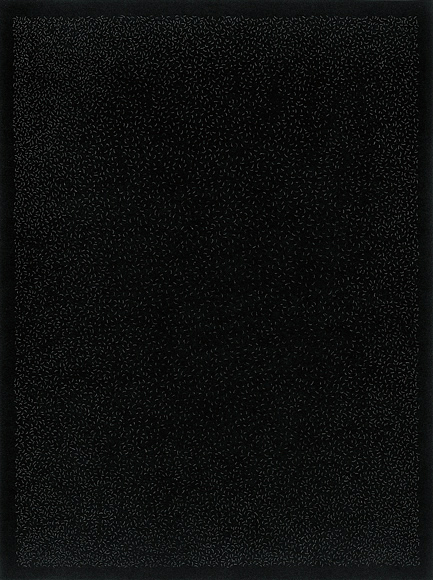

As I drew close, suddenly on the edge of the universe, I then became the edge of the universe: a writhing edge of rich black flames, not the oranges, reds, and yellows of before, now melding into alien unknowable light. Tonguing out into an empyrean realm beyond space, words fail to describe the indescribable. What I experienced exceeded known dimensions, I seemed able to identify five, knowing there were infinitely more, exceeding more than vision or language or image could possibly contain. All feeling, body, location, view, thought, all that was me, vanished. This space/non-space was all, a sense of self or I or me or you was not even a possibility. To speak of rapture cannot describe the all-ness, the silence, the completeness: any of these words are clichés that fall short. I saw golden light in every saturation, in every chromatic possibility, in all intensities, opaque and transparent, like vast steel ‘I’ beams of light shoulder to shoulder but in every dimension so they had no direction, or had all directions, they were everything. And billions of golden spheres of light that had no scale, they could be smaller than atoms or larger than universes. I couldn’t tell. But I know they were souls, souls of all beings reaching behind and beyond time. All were perfect spheres in motion. While I could distinguish form and edge and the shifting changing color and intensity, I knew it was all one light of being. A light structured of infinite photons in multiple dimensions, surpassing meaning. Then I knew and saw into each photon, each revealed its interior as another vast cosmos of black light, a universe of forms, another edge, another empyrean.

© Brian Wood, October, 2018